Dear Amazeball Writers,

I am working on my novel today and thinking about class last night. I am very proud of every one of you for understanding the level of work it takes, not to just publish a novel, but to publish a novel of worth.

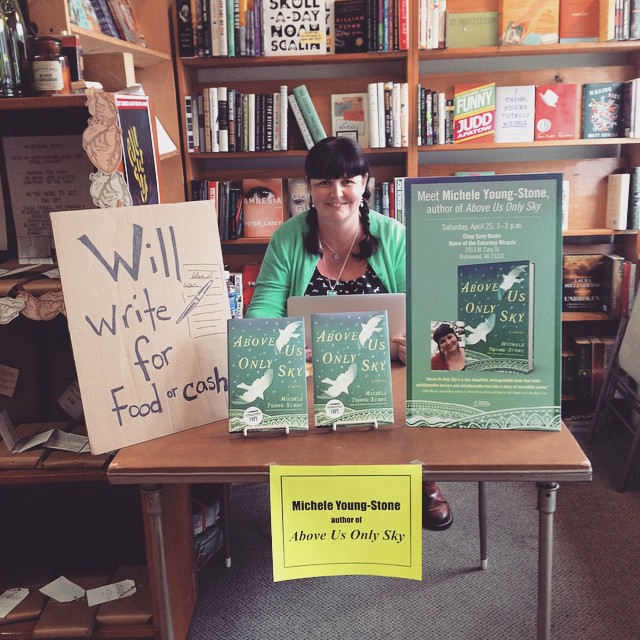

Last year, one of my former students emailed me to say she had good news. She asked if we could talk. Of course, I said sure. We spoke. She told me that she and another former student of mine were starting their own publishing house and they would publish my novel that was rejected by 60+ editors. They are going to publish themselves also.

I was very kind and thanked her, but said no. I didn’t say, “Absolutely not.” I didn’t want to be rude, and I know a romance writer who has successfully gone this route, but I personally (and I think wisely) don’t think it’s a good idea to validate your need to get published by publishing on your own (maybe it’s different if you’re writing formulaic romance), not when you just want to get published and you’re not mindful of publishing really amazing prose. There are more crappy books than good ones. Unfortunately. But, do you want to publish something crappy?

My friend, novelist Susan Gilmore, and I were both represented by Shaye Areheart, a division of Crown Random House. And with her last book, they told her it was “perfect,” not to change a word. According to her, she should’ve known the jig was up. Nothing is perfect. Nothing is ever perfect. Susan’s novel wasn’t ready to be in the world. Her publishing house didn’t care enough about her or her work to dismantle it and make her rewrite. Note: that publishing house, Share Areheart, was about to be dissolved by Random House.

Criticism, whether from peers, agents, or editors, is meant to make us better writers. Criticism is meant to make our work undeniable, something a reader can’t put down. The act of writing is a selfish, amazing act of exploration and creativity. The act of publishing is a business proposition. You can self-publish today, but the question is, “Do you want to publish something that’s just ‘okay’ because it’s a story or has a good character?” No, of course not. You want to publish a work of art, something that makes your reader swoon.

If the only person telling you that your book deserves to be published is you, there’s a reason for that. I feel like everyone here in our class recognizes what’s of worth and is open to making their prose better, and that’s what a real writer is.

“Talent is as cheap as table salt. The only thing that separates a talented artist from a successful one is a lot of hard work.” Stephen King

Now back to the grind.

person–to return to.

person–to return to.

when he had his instant coffee (and late in the day when he had his beer). My father was dying. We were alone in his room, and I’d woken that morning wondering what I could do to get through the day. I got out a rocking chair and that book, which had seemingly disappeared until just that morning (I’d looked for it the day prior), and I sat across from my dad. I said, “We’ll start at page one,” even though “The Cremation of Sam McGee” was our favorite. I was reading from the poem, “The Three Voices,” (p. 8)

when he had his instant coffee (and late in the day when he had his beer). My father was dying. We were alone in his room, and I’d woken that morning wondering what I could do to get through the day. I got out a rocking chair and that book, which had seemingly disappeared until just that morning (I’d looked for it the day prior), and I sat across from my dad. I said, “We’ll start at page one,” even though “The Cremation of Sam McGee” was our favorite. I was reading from the poem, “The Three Voices,” (p. 8)