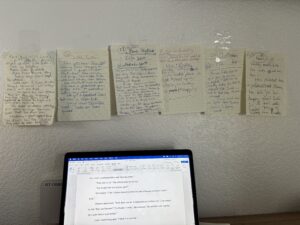

The world, our country, in particular, is a shit-show right now, but I have managed to get away this weekend to focus on my art, which honestly feels like the best, most powerful thing I can do right now.

This novel, my fifth, had a working title of Apothecary, but yesterday I renamed it Witch because it says a lot more. This is my feminist manifesto, a critique of notions of womanhood, the roles to which we’re assigned, the boxes into which we’re placed. It explores the hypocrisy of organized religion and the way in which politicians and religious leaders use religion to justify bigotry and exclusion.

It feels really important and timely.

Originally, I had planned this writers’ retreat this weekend to be an annual event with 8 writers, but after realizing that I didn’t want the responsibility of hosting an event… I simply wanted to write… I canceled the public event and came with a fellow writer, a friend from Richmond, to write and share and chat and write and share and chat.

Next year, maybe I’ll do this again and invite a few more folks to join us. Of course, there happened to be a large Christian Baptist conference of some sort at the hotel this same weekend. I love irony.

I’m teaching a yearlong fiction studio for The Muse Writers Center beginning the end of this month. I’m really excited because I feel like I’ll be leading and working with six writers who will be publishing soon, who are seriously invested in craft. I think that’s all I have to say. … I’m trying to be more “out there” and expressive. I find it far easier to stay to myself.

Dont give up. Write and call your representatives. Be kind to one another.

Here’s an excerpt from Chapter Two.

2

The Witch’s Daughter

She was a girl who went to church. She never imagined herself a witch because she was a girl who went to church, who sat in the second pew from the front and prayed fervently with her eyes shut, who made potato salad with Miracle Whip for Sunday picnics, who baked cookies and sold them at church fundraisers, who changed diapers in the basement nursery and read to the little kids during adult service. She hadn’t met, had only seen the other witch, the one who lived on Cinnamon Mountain and worked at Apothecary on Main Street, the one with black velvety hair and legs white as cream, the one who dressed in thrifted clothes and didn’t go to public school. She didn’t know yet that they were connected. She didn’t know yet that most witches pray the same as her.

This morning, Lola rode her bike to Woodrow’s. She pulled on the barred door of the defunct market, the old sign creaking in the wind, before collapsing, her back against the yellowed cinderblock and opened her sketchbook.

When she drew a place, unknowns emerged. Touching the pencil point to her tongue, her gaze softened; her left hand scribbled back and forth, a room took shape. She opened her eyes and found a countertop, a big jar of red-hot sausages, a pack of candy cigarettes, a glass ashtray with cigarette smoke rising toward the ceiling. In the mirror behind the bar, she saw a velvety couch and a jukebox. She saw her dad. He was good looking. In the mirror, he tousled her hair. How old was she? Four or five?

Lola heard a scratching sound and looked up from her sketchbook at a deer and fawn crossing the cracked asphalt. Rain spit from the sky. She returned to the sketchbook, to her dad on the swivel stool. He smoked a cigarette and tapped the glass where the red-hot sausages floated. She saw herself pretending to smoke a candy cigarette, chewing the filter, and tapping the glass jar of sausages like they were fish and not sausages, like one of them would come to her.

“You’re my dad,” she said to the drawing. She squinted to see him better. “I’m going to find you.” She smudged her father’s face with a fingertip. Probably, he wanted to meet her. Probably, there was a reason he hadn’t been around the last decade.

She looked up at the bulging clouds and packed her sketchbook away. She started for home. The sky turned gunmetal, and the rain came down. She should’ve known better. Her sketchbook was getting wet. She pedaled faster. Every day this summer, the rain had come in flashes, the clouds caught and popping between the mountaintops. She worried for her drawings. If the sketchbook were ruined, would she lose what she remembered of him? She pedaled until she was safely under an awning, the rain blowing in sheets from the west, battering the white swirling letters spelling out Apothecary. She looked through the plate glass window at Susie McMurrer reading a book and pulled the door open. A bell chimed.

Susie was Snow White in the flesh, all creamy skin and black-vinyl hair. Lola was a tan freckle. She held her sketchbook in its army-green bag to her chest. “It can’t get wet.”

“What?”

“My sketchbook.”

“We don’t have plastic bags.”

“I just. Can I just…”

“Yeah. Let me get you a towel.” Susie disappeared in the back, and Lola slid her sketchbook from the bag. Susie returned with three hand towels. Lola took all three and dried the book. “It’s not ruined.” She wiped off her arms and legs. Her feet were black from where the puddled water splashed the backs of her calves and dripped down to her flipflops. Her toenail polish was chipped, and her hands were stained with yesterday’s paint. She held the towels out. “Where should I?”

“I’ll take them,” Susie said. “My mom’s making peanut butter and jelly in the back, and it’s not just any peanut butter and jelly. It’s the best. Her homemade bread, our homemade peanut butter and preserves. Do you want one?”

“How can I say no?” She ought to have said no. She wasn’t supposed to be here. She ought to have left already. If Deb had it her way, the sketchbook would be ruined, but she couldn’t let that happen. She wiped the water from her face. Susie’s back was to her, and she saw the lip balm display. Squat bright tins. She took one and slipped it in her right pocket, letting her heavy T-Shirt fall in place.

“Here we go,” Susie said, returning with two sandwiches.

Lola took a bite. “It’s so good.” She shivered. “I guess the A/C is on.”

“You’d guess right. It was ninety degrees an hour ago.” Susie took a bite of her sandwich and looked suspiciously at Lola. The rain pounded the front glass.

“I hope the awning doesn’t rip,” Susie said.

“I hope not.”

“Do you live around here?” Susie asked. “I’ve never seen you before.”

“Yes. Behind the AG Supermarket.”

“Close by then. It’s weird I’ve never seen you.”

“Yeah. I’ve never stopped by.”

Susie pointed at Lola’s pocket. “You stole a lip balm.”

Lola flushed. “I’m sorry.” She wiped her mouth and took the balm from her pocket, holding it out to give back. When Susie didn’t take it, she set it and the sandwich on the countertop and slid her sketchbook into the wet canvas. There was something seriously wrong with her, this compulsion to take something everywhere she went, no matter how meaningless, not that the lip balm was meaningless. It was a red and pink tin. When the balm was gone, she could put paint in the tin. If she came here every day, she could steal twelve lip balms. She’d have the softest lips ever and the coolest paint containers. Yes, she was a disaster. Total bananas.

Susie followed her to the door. “Why’d you take it?”

The rain blew horizontally against the glass. It seeped beneath the door.

“I don’t know. Please don’t call anybody. My mom will be so mad.” Lola pinched her bottom lip, staring at the door rattling in the onslaught. “I’m really sorry.” Thunder cracked, and the plate glass flashed white.

“Take it,” Susie said. “Keep it.”

Lola shook her head. “I’m really sorry.”

“Your lips are chapped.” She said it matter of fact, like she totally meant it, so Lola held out her hand, and Susie placed the balm there and wrapped her fingers around the tin. They stared at one another. “Stay until the storm passes,” Susie said.

Lola nodded. She pulled her sketchbook out of the wet canvas, and Susie said, “Will you show me what you draw?”

“Sure. Definitely.” She followed Susie to a round table. “This is our occult section,” Susie said. “Some people in town say we’re witches.” She laughed and rolled her eyes.

“My mom thinks that about you. I guess that’s why I haven’t been here until now.” Lola unscrewed the cap and rubbed the peppermint balm on her lips.

“It’s good, right?”

“Really good. It tingles.”

“We grow the peppermint.” Thunder rumbled. Lightning cracked again. “My mom’s friend Mary Hopper does Tarot readings for us. She designs Tarot decks. The cards.”

“What is Tarot?” Lola asked.

“It’s like psychology with archetypal picture cards. Do you know what archetypes are?”

“Not really.” Lola opened her sketchbook.

“Images and ideas that are shared by many cultures, even those that never came in contact with each other. Like Jesus and the holy spirit, like the trinity, like threes. I don’t know. It’s hard to explain.”

“I’ve heard of that,” Lola said, thinking about her art and English classes. “Like the stuff the Indians drew, like sun circles and water.”

“Yeah. Yeah. So, you use the cards to make sense of the world. Each card has different meanings. She passed the Tarot stack to Lola. “Like, this is the Tower. It’s when everything goes to shit, but it also means you get to start over. Try again. The same with death. They have double meanings. All the cards do.”

“The Tower was on top.”

“For you. I could do a reading if you want, but I want to see your drawings.”

“Do people pay money for readings?”

“Sometimes, but it’s mostly intuition.”

Susie and Lola finished their sandwiches, and Lola showed Susie her drawings of Old Woodrow’s Market.”

“I know that place,” Susie said.

“The perspective’s all wrong.” She showed her where she messed up the foreground. “I went there with my dad. Look here.” She turned the page.

“I remember that,” Susie said, “the crazy big sausages, and he sold candy cigarettes. You didn’t just draw that?”

“I drew what I remembered.”

“I have a book of flowers,” Susie said, going to the main register and returning with a brown notebook, dried lavender spilling from its thick pages. “I list and draw the plants. Foxglove is digitalis purpurtea. I collect specimens and list the physical attributes and medicinal uses.”

“How do you know about plants?”

“My mom taught me. Her mom taught her. We’re herbalists. Not witches.”

“And who’s this?” Alice asked, as if on cue, emerging through a burgundy curtain.

Lola looked up. “Hi. I’m Lola. It was raining.”

“You look familiar,” Alice said.

“Mom, can Lola come over after work? I think the sun’s going to come out.”

“If it’s all right with her mother.”

It would never be all right with Deb, but she’d probably work late. She’d probably stop at a bar on the way home, and Lola would be asleep in bed by the time she snuck in after midnight. “It’s fine with her,” Lola said, her attention returning to Susie’s book of flowers.

Susie said, “Lola is an artist.”

“Well, that’s very impressive.”

Lola stayed the whole of the afternoon. Susie was right. The sun came out. At five o’clock, Alice McMurrer locked the front door. Susie counted out the register and Lola offered to sweep and mop. She left her bike chained to a street sign in front of the shop and got in the back of Alice’s Volvo.

On the way to the farmhouse, Susie perched backwards facing her. They rode with the windows down, Susie’s black hair whipping in the wind. Lola’s curls emerging in the humidity. Susie said, “I can’t wait to show you Cinnamon Falls. You’re going to love it so much. And I’ll introduce you to the chickens and our goats.”

Alice made a strange sound, and Susie said, “What?”

“You.”

“What me?”

“Nothing you. You’re very sweet.”

Lola said, “I’ve never seen a waterfall,” and wondered if her mother would ever say that about her to anyone. Had she? No. She didn’t think so. With Deb, she was so often the responsible one. She’d learned to be a disaster from her mother.

“And how is that possible?” Alice asked.

“Huh?”

“You live in a valley. How have you never seen a waterfall?”

“I don’t know. My mom just… Well, my grandmother is more of an indoor person, and my mom’s just really busy.”

“You’ll love ours,” Susie said, before whispering, “are you sure you won’t be in trouble?”

“I’m sure.”

The farmhouse and grounds and waterfall were more incredible than what Susie described. The house had transom windows and a grand staircase. The kitchen was as much greenhouse as traditional kitchen with long vines crowding the plate glass windows. There was a barn with stables where Susie’s grandmother had kept horses. There was a chicken coop and a goat house. To the east of the kitchen was a garden where Alice and Susie grew many of the herbs they used in tinctures and balms in addition to vegetables and fruit. One of Apothecary’s bestsellers for three generations was a blackberry wine said to be an aphrodisiac.

At Cinnamon Falls, they sunned themselves on flat gray rocks, sparkling with quartz. Lola tugged at the bathing suit she’d borrowed from Susie. It was too tight. “How come you don’t go to school?”

Susie exhaled dramatically and bent forward, hooking her fingers around her toes. “My Nana Windborne sent my mom away to school, and she hated it, and she swore when I was born, she’d keep me home. She wants me tied to the land, to the mountain, to the falls. You should hear her give one of her speeches. Our ancestors, Windborne’s mom and dad, Ivy and Burton brought soil from the cemetery in Kilkenny here to Rock Gap. My mom tells the best version of this story, how the white oak they planted grew quickly, how the roots knew to part to receive our dead, how Ivy and Burton were buried beneath it by her and her mom. How there’s meaning and thus God in the land. And on and on. My mom’s…” She stopped to consider how best to describe Alice. “I guess she’s a sentimentalist.”

The sun splashed blue and gold, water dripping off the tip of Susie’s nose, Lola wiping it away. “Come on,” Susie said. They felt there way down into the swimming hole where the falls pooled. Lola shrieked when her feet found a really cold spot.

“It’s Heaven,” Susie said.

“Agreed.”

They returned to the rocks and talked until the sun disappeared behind the tree line. On the walk back, Lola said, “Even if I find out you’re a witch, I won’t stone you or try and make you sink.”

Susie laughed. “Thank God.”

At the house, Lola showered upstairs, and Susie cleaned up in the spare room off the kitchen. “It’s an addition to the original house,” she explained to Lola. “My nana Windborne got to where she couldn’t climb the stairs.”

By flashlight, Susie led Lola to the garden where they picked tomatoes and green peppers from the vine, setting them in a wooden bowl and taking them back to the kitchen. They made spaghetti with marinara and ate at ten o’clock. Alice’s gray streaked hair was twisted and pinned on top of her head. Alice said, “I don’t think your grandmother would like the fact that you’re here.”

Susie looked at her like she’d lost her mind.

“I’m just saying… Lionella Brewster was never a fan of my mother’s. I remember my mother dragging me places before she sent me away to school: to the park and to Rock Gap Baptist, and it was just very uncomfortable. We left halfway through the sermon. Not even halfway.”

“She doesn’t live with us,” Lola said. “She’s at Agatha’s House.”

After Alice went to bed, Lola changed into a pair of borrowed pajamas. They too were too tight. Susie got a shopping bag from her wardrobe and toted it through the window onto the slate roof. “My great grandparents designed the house. It’s totally bizarre.”

“I love it.”

“Oh, me too. It’s just weird. The roofs are all different angles. I don’t know.” She pulled a pack of cigarettes and a bottle of red wine from the bag.

She flicked a Zippo, lighting the cigarette and exhaling smoke rings, before passing it to Lola, who coughed. “My dad was a smoker,” Susie said. He kept cartons of cigarettes in our big freezer. “I started smoking after he left.”

“Where is he?” They passed the cigarette back and forth.

“No idea. He sort of lost his mind.” She shrugged and took a swig of wine. “My mom says wine is the lonely woman’s lipstick.

“What does that mean?”

“No idea. Maybe how it stains the lips.”

Lola took a swig from the bottle and immediately felt guilty. She hated drinking. Her mother was a lush. She took another swig and another waiting to feel something. Good? Finally, she felt a warmth settle over her and found her head on Susie’s shoulder, her hands in Susie’s hair. “You’re so pretty,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to meet you.”

“Seriously?”

Lola drank some more. “I think it’s all gone.”

“I have more. It’s one of the benefits of being homeschooled. I spend a lot of time here, lots of time to kill, to stash things. I’ll open the blackberry wine next. It’s sort of sweet, but it’s really good. I like sweet.”

“Me too.”

“My mom says wine palettes change as you age. Everyone starts off loving the sweet, and then their palate develops.”

“You’ve lost me.”

Susie said, “My dad thought my mom was trying to poison him. He started opening bottles and pouring them out. He wasn’t well.”

“My dad’s married and has three kids. He was around for a while. I sort of remember him, but my mom won’t tell me anything about him.”

“My mom was the same. She didn’t know her dad.”

“What’s wrong with men? With fathers?”

“Mine was really good until he wasn’t.” Susie put the bottle to her lips. The cicadas clicked around them.

Susie’s room had a four-poster queen-size bed and an antique vanity. They listened to Susie’s favorite albums by the Cure and the Smiths. Susie kept her windows open which was weird to Lola, who was used to shut windows, the thermostat at seventy-two degrees.

When Lola fell asleep, the lights were on. She could hear the night outside and the record inside. She dreamed her dad was pulling up to the duplex and getting out of his car. He’d come for her. She woke having to pee. It was three in the morning. Her mouth tasted disgusting. Her leg was thrown over Susie’s. Her face was in Susie’s hair. An owl hooted. Everything about Susie and Cinnamon Mountain felt like home.