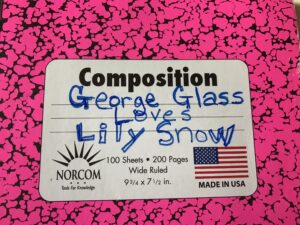

I started writing my fourth novel three years ago this month, maybe this very day. It’s been titled George Glass Loves Lily Snow, The Reinvention of Amy Brown, the working title The Reimagining of Amy Brown—because the whole thing needed to be reimagined, and finally, The Hummingbird. My past three novels have had long titles, so maybe it’s time for a short one.

What do I want now?

I want to show you the seven-plus notebooks with every page full. I want to show you early drafts with telekinesis and doors exploding off hinges. I want to tell you the life story of every character in my novel because I know them. I want to tell you how Elisenda swallowed the emeralds and held them in her gut until she soaked in a tub in Barranquilla and passed them into the lukewarm water.

I want to tell you that the main character’s mother used to be his grandmother, and after I made this change—from grandmother to mother, the members of the novel-writing group I was leading, were sorely disappointed. They really liked the grandmother. I’d liked her too, but writing is a process, and one of the things I realized was that this book was my most autobiographical, and I was afraid to make George’s grandmother his mother because it was too close to the truth, to holding up the mirror, and as you know, nothing is better than the truth. The core of all good fiction is its truth. Novelists tell more truths than memoirists. We just don’t admit to anything.

George’s mother wasn’t sympathetic like his grandmother. She was selfish how mothers can sometimes be.

At one point in the evolution of this novel, George’s foster mother was his sister, but again, it was like I was writing around what needed to be written, what had compelled me three years ago to abandon my historical novel-in-progress to tell the story of George Glass, a boy who loses his mother and has to navigate the world without her. Not only does George lose her, but it turns out she was never the woman she claimed to be. He, and the police, have no idea of her true identity.

I want to tell you how much my father’s cancer and his passing influenced this novel, and how much my love for my son, and my willingness to do anything to protect him, influenced this book. I want to tell you that I know, like the dead woman in my book, that I am selfish, that if I could keep my teenager young forever, I would do it. I’d consider consequences, but it doesn’t seem so bad—despite Tuck, Everlasting—no one growing up, no one getting old, no one dying. This might be the most honest novel I’ve ever written.

With every new book, there’s a new adventure. Every time, I hope the process will get easier, but it never does because each book is its own beast, its own treasure, a unique act of discovery. If you’re not putting down layers and scraping them away, you’re not really learning anything. You’re not, as John Gardner wrote in The Art of Fiction, making art.

This novel, like all of them, was an adventure.

I want to tell you about the miracle that happened when my father died, the miracle I was in too much grief to admit to for over a year, because a miracle flies in the face of anger. A miracle crushes anger. I was reading from The Collected Poems of Robert W. Service, a book my father used to read to me early in the morning  when he had his instant coffee (and late in the day when he had his beer). My father was dying. We were alone in his room, and I’d woken that morning wondering what I could do to get through the day. I got out a rocking chair and that book, which had seemingly disappeared until just that morning (I’d looked for it the day prior), and I sat across from my dad. I said, “We’ll start at page one,” even though “The Cremation of Sam McGee” was our favorite. I was reading from the poem, “The Three Voices,” (p. 8)

when he had his instant coffee (and late in the day when he had his beer). My father was dying. We were alone in his room, and I’d woken that morning wondering what I could do to get through the day. I got out a rocking chair and that book, which had seemingly disappeared until just that morning (I’d looked for it the day prior), and I sat across from my dad. I said, “We’ll start at page one,” even though “The Cremation of Sam McGee” was our favorite. I was reading from the poem, “The Three Voices,” (p. 8)

But the stars throng out in their glory,

And they sing of the God in man;

They sing of the Mighty Master,

Of the loom his fingers span,

Where a star or a soul is a part of the whole

And weft in the wondrous plan.

Here by the camp-fire’s flicker,

Deep in my blanket curled,

I long for the peace of the pine-gloom,

When the scroll of the Lord is unfurled,

And the wind and the wave are silent,

And world is singing to world.

My father and I were alone, and I knew he was gone. I knew that he had wanted me there to help send him on his way. I knew that he was a part of that firmament.

I want to tell you that this novel is for him. It’s for all of us who love, who grieve, who mourn, and who survive.

I don’t think I’m very good at “writing blogs” because I like to disguise my truth in fiction, but I needed to share the process of writing this novel and how important it is to me and what a journey it’s been thus far.

And I have lots more to share. To be continued…